Author Curtice Discusses Personal, Collective Storytelling as Groundwork for Dismantling Racist Systems in Opening Keynote of CHHSM Annual Gathering

CHHSM’s 83rd Annual Gathering, held online March 2-4, 2021, focused on the theme “Together in Hope.” During the opening keynote address from noted author Kaitlin Curtice, the theme quickly expanded into the hope of beginning anew to build a more just, caring and compassionate world.

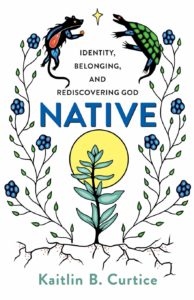

Curtice is an enrolled citizen of the Potawatomi Nation — a federally recognized tribe of the Potawatomi people located in Oklahoma — and someone who grew up in the Christian faith. Her address centered on her latest book, Native: Identity, Belonging and Rediscovering God, which details how reconnecting with her Potawatomi identity both informs and challenges her faith. Using the book’s framework, Curtice discussed storytelling, why telling our own stories — and our collective story — is important, and what it means to have hope, especially when that hope is beginning again in the face of an unknown future.

“Kaitlin shared her story of being part of the Native American ancestry, and did a wonderful job highlighting the importance of honoring every cultural story, which impacts how we best serve others,” said the Rev. Dr. Sheila Guillaume, pastor of Union Congregational UCC in West Palm Beach, Fla., and a CHHSM board member.

The ancient Potawatomi Flood Story was the framework for Curtice’s presentation. In the story, the Creator has flooded the earth and there is no land left. A few animals float around on a log, grieving the loss of their world. But eventually, they are ready to begin again and make a new world. An unremarkable animal, Muskrat, volunteers to go to the bottom of the water and bring back earth to rebuild the land. He dies in the process, but the other animals find dirt clenched in his paws and thank Muskrat for his sacrifice. Then Turtle volunteers his shell, and the animals take the dirt from Muskrat and place it on Turtle’s back, creating Turtle Island (what the Potawatomi call North America).

The story “helps us ask a lot of questions,” said Curtice. “What does it mean to begin again … what does it mean to grieve what has been lost and to dream of a new world?”

The Potawatomi Flood story is one example of the stories we carry within us, Curtice said. “Indigenous bodies … carry stories inside us, not just stories of oppression, but stories of liberation, of renewal, of survival. The sacred thing about being human is that no matter how hard we try to get rid of them, our stories are our stories. They are carried inside us … they are the tools we use to explain ourselves to one another, to connect.”

Curtice explained that her moment of epiphany — of realizing the stories, both good and traumatic, within her — began on a cold January day in Atlanta while hiking at Sweetwater Creek. She had a moment “when the lens of my life zoomed out, and I saw truly for the first time what Potawatomi people once experienced — a history of forced removal from Indiana into Kansas, [along] something called the Trail of Death … I knew that the journey ahead of me would be different than the one behind me.”

Her Sweetwater Creek epiphany created a hope “that transformed the entire world right before my eyes, and brought me back to myself in a way that I’d never known was possible,” Curtice said. “That brought me to the reality of a God who sees and gives us the gift of seeing.”

“This is where the importance of storytelling comes into play,” she added. In creatively seeking our own personal creation stories, said Curtice, we are searching for an oft-times painful and messy — but lifechanging and lifesaving — truth.

“Searching for truth means that we’re honoring our beginnings, we’re honoring our stories,” Curtice said. “There are two ways in which storytelling is really important. … First is telling our own story. Second is telling the collective story that we’re a part of.”

Curtice stressed the importance of figuring out what our own stories are rooted in. “Are they rooted in love and solidarity and connectedness? Are they rooted in hate? Are our stories plagued with things like colonization and white supremacy?” she asked. “Well, if we live in America, the answer to that one is yes.”

“Just as we remember our own creation stories, we have to remember the creation story of America, that this is a nation that was built on the back of Indigenous and Black bodies, an America that has abused some and upheld the sheer success of others,” Curtice added. “So even our personal narratives have been affected by systems of whiteness and hate. And our work is to own and understand those stories inside our bodies. That is where the hard work begins. Our storytelling involves deconstruction, and examining the systems that we grew up in.”

Curtice cited Dr. James Cone H. Cone (1938-2018), the founder of Black liberation theology who was the Bill and Judith Moyers Distinguished Professor of Systematic Theology at UCC-related Union Theological Seminary in New York City. In an interview, Cone said, “I read the Bible from the bottom.” This means, said Curtice, that we tell the stories of people who are forgotten.

“Resisting hate within our families and communities means that we choose to tell a better and truer story,” she said. “I think about Jesus, who was a storyteller, who came and told a different kind of story. His parables tended to turn things upside down … made sense of things that no one was expecting … with stories that brought the small and the forgotten and the oppressed right to the center. That’s how communities are transformed.”

In examining our personal and collective stories, the next step, said Curtice, is thinking “about the ways that you want to bear fruit in your world, in your community, in your family, in the world around you.”

Curtice found one way to bear fruit through a “Be the Bridge” church group. Be the Bridge was created in 2016 by Latasha Morrison as a space to encourage racial reconciliation among all ethnicities, to promote racial unity in America, and to equip others to do the same. Through the local group at her church, Curtice said, “I learned that Black and Indigenous women must work together, partner together, and actively join with other women of color to lead the way forward in America. … Bridging the gap means having more conversations on intersectionality within our churches and communities. It means men stepping down and women stepping up to tell our stories.”

Curtice reiterated that these kinds of intersections among women of color help participants “remain willing to do the work necessary to make justice happen, especially within the church.”

“In America, Black people, Indigenous people, other people of color and religious minorities have run out of time,” she said. “There’s no more time to tiptoe around conversations … There is no more time for Indigenous bodies, women’s bodies, trans bodies, sick bodies, Asian bodies, disabled bodies, or Black bodies to be attacked; and for everyone to misunderstand why it happened.”

“This is the America we know, and have always known. History tells the story,” she added. “And if we can’t gather in a living room to tell the truth and listen to one another, we will never gather in the streets or in our churches or in our political spaces to ask for change. It must begin with our experiences with our words, with our bodies, and lead us to a better way forward.”

Curtice noted that there is reason for hope as people of all religions and races and cultures are finally naming injustice and practicing solidarity. But, she said, “We have to remember it’s not a ‘fad.’ This is work that is meant to last. It is lifelong work. It takes time and energy to keep it going.”

Centering in on solidarity, Curtice asked, “What is our solidarity rooted in? Is it that Black lives matter? Is it that America needs to face its own history? Is our humanity itself our common ground? Is it our belief in God? What brings us together? Is it our sacred breath, the breath that is taken too soon from some of us by violence and hate and police brutality?”

She then discussed decolonization as a tool for imagining a better world. By examining how to break down or dismantle the long-standing colonial systems around us, and listening to those who have been marginalized, we can become part of making the world better, she said.

As with the Potawatomi Flood story, the current COVID-19 pandemic has washed away how we were and the future offers the opportunity to create a new world. “Historically, pandemics have forced humans to break with the past and imagine their world anew,” Curtice said. “This one is no different. It is a portal, a gateway between one world and the next. We can choose to walk through it, dragging the carcasses of our prejudice and hatred … or we can walk through lightly with little luggage, ready to imagine another world and ready to fight for it.”

“What do we imagine is on the other side” of the pandemic, Curtice asked. “A world where Black and Brown children can play freely; a world where queer and trans people are accepted and loved for who they are; a world where disabled people aren’t controlled by ablest laws and ideas; a world where women can speak without patriarchy and misogyny taking over our words or silencing us completely.”

“We choose to have hope because those who came before us never stopped dreaming of a future,” she said. “And here we are, dreaming.”

Curtice summed up her talk with three ways to embody hope.

First, she encouraged attendees to “recognize how much systems of whiteness steal from everyone” and urged them to expand their circles by decentering whiteness.

“My friend, Gabes Torres, says this: Being anti-racist, anti-colonial and anti-capitalist doesn’t only mean restoring our humanity in actionable and strategic ways, but falling in love with it again,” Curtice added. “This is exactly it. We get to fall in love with our own humanity when we choose to widen our circles of understanding and solidarity to include those that white systems do not include.”

Second, Curtice said, is returning to the gifts of the earth. This can be as simple as drinking enough water, she said. Taking the time to place ourselves under trees and in nature teaches us to be humble, she added.

Finally, she said, is self-care. “Practicing self-care and self-love is actually a very revolutionary act.” Such a practice helps us to become grounded in the work we have set out to do that affects all the people and systems around us, Curtice said.

“For me, Kaitlin Curtice speaking about ‘reading the bible from the bottom up’ was one of the best parts — certainly the best way to open the Annual Gathering,” said Paula Barker, CHHSM’s executive assistant for events and administration. “I so enjoyed her, and can’t wait to jump into CHHSM’s Together We Learn Book Group that will be discussing Native later this month.”

Throughout Curtice’s talk, Annual Gathering participants shared a vast number of questions and positive comments through the live keynote chat, which Curtice answered in a Q&A session following the presentation.

Stacey Parke, executive director of Orion Family Services in Madison, Wis., found wisdom in Curtice’s words on the COVID-19 pandemic offering a chance to restart. The pandemic offers a chance to “break from the past and an opportunity to embrace the world anew. We are ready to imagine a new world and work for it,” Parke said. “Indeed, we MUST create lasting change because of the inequities and disparities that we can no longer hide from.”

The Rev. George Graham, vice president of CHHSM, noted the importance of epiphany experiences. “In sharing her own epiphany experience, Kaitlin Curtice invited us all to tell the stories of those life events that make the journey ahead different than the journey behind, and to tell those stories,” he said. “She encouraged us to look ahead with hope and expectation and think about how we wanted to bear fruit in our community, family, and world. She challenged us to rethink the world as it exists, to do the hard work of decolonizing, and to imagine the world anew.”

Read the opening keynote from author Kaitlin Curtice.

Read about the opening worship with the Rev. Darrell Goodwin, and closing worship with the Rev. Dr. Yvonne Delk.

Read about the Annual Gathering from beginning to end.

Learn more about and join CHHSM’s Together We Learn Book Group, which begins March 25. All are welcome!

Join Our Mailing LIst

"*" indicates required fields

Follow on Facebook

New Resident Finds Belonging at Emmaus Homes - CHHSM

www.chhsm.org

Heather’s journey toward independence has been nothing short of inspiring. Since moving into her new home last year, Heather’s world has expanded in ways she never imagined. Leaving the familiarit...