Annual Gathering Keynotes Address Aspects of Moving Forward Together in Becoming Anti-Racist

Among the highlights of the recently concluded 84th Annual Gathering of the UCC’s Council for Health and Human Service Ministries (CHHSM) were the three keynote addresses. The keynotes were delivered by the Rev. Dr. Alton B. Pollard III, president of Louisville Presbyterian Seminary; Dan Hermann and Lisa McCracken from platinum sponsor Ziegler; and Nikki Lanier, owner of Harper Slade, a racial equity advisory firm.

Though different in style and tone, all three presentations took to heart the Gathering’s theme, “Forward Together,” in addressing aspects of systemic racism and becoming anti-racist. Q&A sessions with the audience followed each keynote.

Pollard delivered the opening keynote, “Racial Justice, Public Health and Our Current Struggle,” the morning of March 9. Before he launched into his speech, he took time to thank CHHSM, the Council for Racial and Ethnic Ministries (COREM) and the UCC for passing last year’s resolution on racism as a public health crisis.

The resolution has caused people to “reflect on things that seem separate to many people,” Pollard said. “We cannot begin to think about public health outside of an anti-racism platform. For all you do in your work as CHHSM, I am grateful.”

Pollard Identifies Church in the Wild

A 2011 video — “No Church in the Wild” by Jay-Z and Kanye West — opened Pollard’s remarks and, indeed, set the tone for his message. Pollard lifted up the refrain: “What’s a mob to a king? What’s a king to a god? What’s god to a nonbeliever who don’t believe in anything?” The song was prompted by the Occupy movement of 2011, but the message is still relevant today, he said. “I think it speaks volumes to where we are today in our world today — forms of hierarchy, forms of oppression, forms of faith. … It is hard not to be traumatized if you are young by the crashing waves of racism, exhaustion and rage.”

“Today, Brown, Black, Latinx, and white children are growing up measured not in terms of years but in the thickness of trauma they have endured,” Pollard said. “They have known a world made hard and opaque by our racism, sexism … they do not always know they have access to liberative resources — little lived experience or aspirational capital to envision a meaningful future.”

But, he said, “Transformational change comes from the recent past and establishes its own distinctive way forward. Today, at the vital intersection of COVID and the criminalization of Black and Brown bodies, a new movement has been recognized, the momentum seized. In the wild. Out of our endemic racism the body politic has been challenged to be anti-racist as never before. The list of deaths over time resists the attempt to relegate them to ‘isolated incidences.’”

Speaking within days of the two-year anniversary of the death of Breonna Taylor in Louisville, Pollard looked to the new movement as being church itself. The movement, he said, “embraces all people — exquisite Black, Brown, and white people” and is “led by young people, many of whom are queer or trans, and absolutely affirming of their own sense of faithfulness. It may not look like church, but it is very much church.”

“They are doing church outside the walls of power on the streets, and in social media,” he added. “They recognize that all manner of intersectional oppression is alive and well and will not be eliminated without a sustained mass challenge. … It is the Black, Brown, and disaffected bodies of youth creating change.”

Pollard cautioned that change is slow, and often may not even be accomplished in a lifetime. He quoted Coretta Scott King, who said, “Struggle is a never-ending process. Freedom is never really won. You earn it and win it in every generation.”

But, he concluded, “radical practices of love and inclusion begin by believing in the infinite worth of every human being everywhere.”

Pollard encouraged his audience to “model sanctuary with one another because the safest place that I long to be in this world is in another person’s heart. When faith meets public health, we have reason to hope. And I want to simply say to you, all evidence to the contrary, God is in the wild, and we must be there, too.”

Boards and Leadership Must Be Diversified

The second keynote came Wednesday afternoon, March 9, as Dan Hermann, president and CEO of Ziegler, and Lisa McCracken, Ziegler’s director of senior living research and development, gave a presentation on diversity’s role in governance.

In developing diversity, there are several things that must be accomplished, said McCracken. Look at board composition, she said. “Look around you,” she said, and ask “What does our board look like?” Such factors as experience and background also need to be examined, she said. Lack of board member term limits or requirements for being on the board (e.g., being part of certain organizations, for example, can hinder board diversity). “Do you populate to govern who you are now or where you’re going,” McCracken asked.

McCracken also encouraged CHHSM members to look at how diversity in thought is expressed and accepted on boards and suggested structuring discussions to solicit diverse viewpoints. Finally, she said, board composition should mirror an organization’s consumer base but also its workforce diversity.

“Committing to diversity in governance requires change,” McCracken said. By 2025, she said, millennials will represent some 75 percent of the global workforce. Quoting a 2018 study by Deloitte, she added, “Millennial workers have a better perception of leadership of diverse and forward-thinking companies. They see these work environments as more motivating and stimulating.”

The present, added Hermann, is an opportunity for faith-based nonprofits to stand out in the market. To survive, the ability to attract and retain talent is of prime importance, he said.

Hermann also discussed the role of faith in sponsorship transitions, or growth through partnerships. In the past five years he said, 80 percent of not-for-profit to not-for-profit sponsorship transitions have been among faith-based providers.

He encouraged boards and leadership teams to take a proactive stance regarding growth of their organization in order to determine whether the organization can grow alone or in partnership with others.

The Time to Explain Racial Equity without Action is Past, says Lanier

Lanier rounded out the keynotes, delivering the closing address the morning of March 10. Titled “Beliefs, Bias, and Behavior: Making the Case for Racial Equity,” her talk drew out the “inextricable link” between race and economics, and centered on the need for radical racial equity. “Inequity and racism are macro-economic issues,” she said.

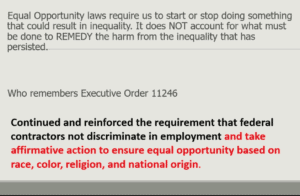

Equality and equity “are used too casually and not with the rigor necessary,” Lanier said. “Equality has had its place in our historical construct. Equal rights laws have not eliminated racial discrimination or marginalization or bias. They are examples of pursuit of equality but not attainment of equality.”

“The pursuit of equality will and has hampered the U.S. economy,” she added “Equality is a heart condition. It’s about a belief system, and you can’t legislate belief. You can try your best to legislate actions, but you can’t legislate beliefs.”

Change, she said, must come through capital systems. By 2045, Black and Brown people will be the majority of people in the work force,” Lanier said, and that will require Black and Brown people accessing the middle classes.

Lanier pointed out that when judging how the economy is doing, people look to the middle class. She added that by 2045 — for the first time in history — we will be relying on Black and Brown people to buoy the economy.

“’The right thing to do’ arguments don’t compel capital systems,” she said. “To disrupt fundamental systems to embrace racial equity requires more. Every structure and system must be changed.”

Such changes often meet resistance. Lanier cited Executive Order 11246 — affirmative action — signed into law by President Johnson in 1965. Although the order was “the closest we’ve ever come to remedial action regarding systemic racism,” it was and still is met with extreme resistance.

“It’s harder for many people to understand the context in which remedial affirmative action must sit — and it’s a context of understanding what’s happened to Brown and Black people in this country,” Lanier said, “and in a country where we don’t teach anything really about Black history. There is no context, and so we talk about affirmative action without any context.”

Racial equity is “proportional fairness that takes into full account the cultural and historic realities facing people of color, as distinct from all other people, and works to remedy the same,” Lanier said. “To be a racial equity advocate means that you acknowledge that something has happened and its cumulative effect is not your fault, but the continued impact of which impacts more than me.”

Racial equity is not just stopping racism, but also stopping the bleeding and treating the wound that has become infected, she said.

“Most Black and Brown people carry around with them a narrative of deficit, a narrative of decline, a narrative of ‘less than,’” Lanier added. “Our mattering happens in context, with asterisks, with footnotes, that we are rarely in control of.”

In bringing diversity and inclusion into the workplace, she said, and assuring that it is fully activated and amplified, those with deficit narratives will believe they are safe and become engaged.

“The browning of the country requires a new and acute understanding of Black and Brown dynamics in and at work,” she said. “We can’t afford to spend any more time ‘selling’ the need for racial equity. We must acknowledge the need to stop and cure AND recognize that it will feel ‘set aside-ey’ to many people.”

“We ALL inherited [systemic racism]. No one caused it, including white males,” Lanier said during her Q&A session, so “approach the work with grace and empathy. Keep one foot on the gas, but treat people with grace and empathy.”

Or, as Pollard remarked during his Q&A session, “Salvation in its original derivation means ‘health.’ Our church communities need to be places of health and healing and sanctuary. And bold and outrageous. … Our job is to ensure that children of God everywhere have access to the God within themselves for whatever form of healing and wholeness and wellbeing they need. In that, we will begin to see the healing of a nation that does not yet know itself.”

Join Our Mailing LIst

Follow on Facebook

Iredell Adult Day Services Hosts Ribbon-Cutting to Celebrate Adult Day Health Certification - CHHSM

www.chhsm.org

Iredell Adult Day Services (IADS) in Newton, N.C. — a nonprofit organization dedicated to caring for older adults, vulnerable groups, and their families, and part of EveryAge — hosted a ribbon cut...